Social Capital and its impact on individuals’ and societies’ rational choices and quality of life

Keywords: Social Capital, Individuals, Society, Community, Rational Choice, and Quality of Life

Abstract

Social capital, a concept that derives advantages gained from social relationships, plays a crucial role in individuals’ and societies’ rational choices and quality of life. This paper examines how social capital facilitates rational decision-making among individuals and communities while comparing the arguments of sociologists James Samuel Coleman and Pierre Bourdieu on the topic. The study explores various dimensions of social capital, including bridging and bonding social networks, and its relation with human and physical/financial capital. Coleman’s rational choice approach views social capital as an individual resource, while Bourdieu’s embeddedness approach focuses on its impact on groups and social inequality. Empirical analyses demonstrate the positive impact of social capital on individuals’ well-being, educational achievements, and overall quality of life. Strong social capital enhances cooperation, lowers transaction costs, fosters empathy, and improves the flow of information within communities. However, criticism is directed at the limited consideration of power dynamics and gender disparities in some social capital theories. Ultimately, social capital proves to be a valuable resource that contributes to the development and prosperity of societies. Its effects on decision-making, resource distribution, and individual well-being highlight its significance as a multidimensional concept in the study of social systems. The paper calls for a nuanced understanding of social capital, considering the complexities and context-specific factors that influence its impact on individuals and societies

Acronyms

QoL Quality of Life

SCI Social Capital Index UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

US United States

WHO World Health Organization

Introduction

Social capital, a concept deriving advantages from social relationships, operates much like financial capital, utilizing beneficial social bonds to acquire knowledge, resources, and other forms of capital through productive work and regeneration (Krishna and Uphoff 2002). James S. Coleman aimed to integrate rational choice theory with the study of social systems, preserving the significance of social structure (Coleman 1988). This paper explores how social capital facilitates rational decision-making among individuals and communities and compares the perspectives of sociologists Coleman and Bourdieu on this topic. It also assesses the impact of social capital on individuals’ and societies’ quality of life, conducting a critical analysis of related theories and arguments.

An overview of Social Capital and its examples

“Social capital” encompasses various measures of trust and reciprocity among members of a networked community and organizations. Social relationships are composed of multiple sources, such as family, work, community, and other social networks, all of which significantly influence social identity and the exchange of goods, services, and information (Letki 2008). According to Robert Putnam, social capital can be categorized into two main types: bridging social capital, characterized by inclusive and outward-looking social networks, and bonding social capital, involving exclusive and inward-looking social networks. Putnam also identified seven dimensions of social capital, including political participation, civic participation, religious participation, workplace networks, mutual trust, and altruism (Putnam 2000).

Moreover, the diagram below illustrates some exemplary instances of social capital in today’s world.

Social Capital and its relation with Human Capital and Physical/Financial Capital The theory of social capital extends human capital theory, which in turn abstractly

extends physical and financial capital (Smith et al. 1992). Human capital is made up of individual abilities, talents, and knowledge, while social capital is made up of individual relationships and networks of connections and interactions. Social capital is an inherently ambiguous notion as it originates in the interpersonal relationships between people (Coleman 1988). It is an enabler of productive and economic activity, just like physical and human capital (Coleman 1988). Trust and trustworthiness are examples of social capital in the sense that groups with such attributes may achieve more than those without them.

Two major schools of thought on Social Capital (Rational Choice and Embeddedness) In the literature on social capital, there are two distinct schools of thinking. The rational

choice perspective views social capital as a resource for individuals formed by their rational choices, while embeddedness focuses on how social capital affects individual members of a group and how groups of individuals create social capital (Whitham 2007). James S. Coleman developed the rational choice approach to social capital, aiming to integrate sociology and individual social actions with economics’ rational views. His definition of social capital emphasizes its multidimensionality, identifying three features of social interactions that allow people to use them as a resource: information channels, norms and effective sanctions, and obligations, expectations, and the trustworthiness of structures (Coleman 1988).

On the other hand, the embeddedness approach sees social capital as a macro-level resource accessible to groups, such as communities and governments. Pierre Bourdieu explores social capital as a group-level resource anchored in networks, facilitating social mobility and the reproduction of class relations. Bourdieu’s work recognizes social capital as a connection to other types of capital, enabling individuals to access financial or cultural resources for their advantage (Bourdieu 1986).

A comparative analysis of Coleman’s and Bourdieu’s arguments on Social Capital Coleman and Bourdieu both consider social capital as primarily rooted in social

interactions, but their perspectives differ significantly. While Bourdieu focuses on social capital’s connection to status and power, highlighting its unequal distribution among individuals, Coleman views it as a public good benefiting the entire community. Coleman’s approach emphasizes social capital as a result of social structure, overlooking power dynamics and conflicts, unlike Bourdieu’s theory that addresses the concept of “cultural capital” as collective property traits (Bourdieu 1986).

Coleman’s argument aligns with rational choice theory, explaining human behavior through logic and rationality within a specific social framework. He contends that social capital acts as both a public and private good, benefiting not only those who form the groups but all members within the network (Coleman 1988). For example, a neighborhood watch group

formed to reduce local crime benefits the entire community, not just the direct participants. Furthermore, Coleman sees social capital as a constructive force, enabling actors to achieve otherwise unattainable goals. He illustrates this with the example of New York’s wholesale diamond dealers, where trust and honesty among members facilitate diamond

inspections without formal agreements or insurance (Coleman 1988). In contrast, Bourdieu’s perspective highlights social capital’s role in reinforcing social inequality. In summary, while Coleman and Bourdieu both contribute to the understanding of social capital, their differing viewpoints on its nature and effects create complexity and debate in the literature.

Impact of Social Capital on individuals’ and societies’ quality of life (An empirical analysis) Social capital’s influence on individuals’ and societies’ quality of life is evident at both

the family and community levels. At the family level, social capital is reflected in the relationships among family members. The presence and interactions of parents significantly affect the transfer of human capital to their children. Regular communication and engagement between parents and children enhance the family’s human capital (Smith et al. 1992).

On the community level, social capital encompasses norms, networks, and interactions that influence a child’s educational progress. Intergenerational closure, as coined by Coleman (1990), refers to the beneficial engagement between children’s peers and their parents’ social circles. This interconnectedness with other adults in society fosters support for norms and values conducive to educational achievement.

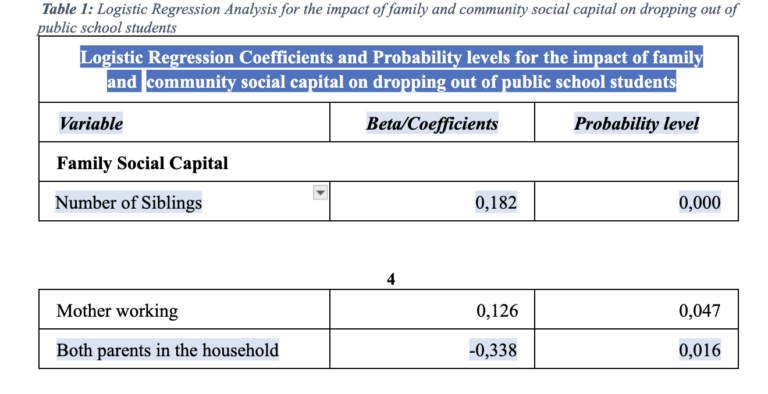

Empirical studies, such as the one conducted by Smith et al. (1992), provide valuable insights into the impact of social capital. For instance, this study explores the effects of human capital and social capital on high school dropout rates, demonstrating the significant role of social capital in shaping educational outcomes at both the family and community levels.

The table below shows a brief logistic regression analysis of the study.

According to the empirical analysis by Smith et al. (1992) on the impact of social capital on high school dropout rates, several variables were found to be statistically significant and correlated with dropout levels. The presence of both parents in the household, mother’s college expectations, involvement in church activities, and parent interest in the child’s school matters were negatively correlated with dropout rates, indicating that a stronger presence of these elements reduces the likelihood of students dropping out. Conversely, the number of siblings, mother working, and the number of moves since grade 5 were positively correlated with dropout rates, suggesting that an increase in these factors leads to a higher dropout rate. Other factors, such as student talk with parents, involvement in youth activities, and school bond/tax increase issues, were not found to be statistically significant in the study.

Furthermore, social capital has been linked to better mental and physical health outcomes. Individuals with higher levels of social capital tend to exhibit greater resilience against stress, anxiety, depression, and diseases (Putnam 2000). Quality of life (QoL) is a multifaceted concept, extensively studied in various social science fields, including economics, sociology, psychology, anthropology, and political science. QoL encompasses various aspects of life, such as economic opportunity, health facilities, environmental sustainability, access to cultural and recreational programs, and low crime (Lauer 1978). Measuring the quality of life involves examining multiple domains, such as health, mental health, well-being, housing, family, governance, and community (Veenhoven 2002). The indicators and domains used for measuring QoL are vast and diverse (Walker and Maesen 2004).

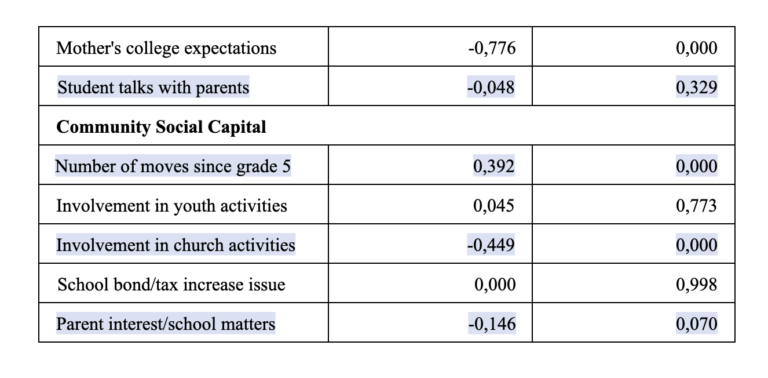

The table below depicts a correlation between the social capital index1 and quality of life index when the top ten nations in terms of quality of life are considered (The World Bank 2021).

The table implies that there is a significantly high and positive correlation between the social capital index and quality of life index, indicating the impact of social capital on quality of life and vice versa.

Likewise, the figure below indicates a comparative analysis between social capital and quality of life indices in the top 10 countries in the world in terms of high living standards.

1 Social Capital Index (SCI) is an index that measures social cohesiveness and involvement, community and family networks, political engagement as well as the level of trust in institutions (The World Bank 2021). There is a range of 0 (low) to 100 on this scale (high).

The graph demonstrates that nations with higher social capital have a better quality of life. Hence, there is a positive association between social capital and the quality of life in different nations.

Moreover, to compare the social capital index in developing nations with the world’s developed nations, the graph below reveals the social capital index in some of the developing and developed countries between 2017 and 2019.

The graph illustrates that developed countries such as the US, UK, Germany, and France have a higher social capital index in comparison to developing nations like Central Asian countries, China, India. While, Russia, Turkey, Japan, and South Korea demonstrate a moderate level of the social capital index.

Positive Effects and Benefits of social capital on society

Social capital has been associated with various dimensions and offers several advantages. Firstly, it facilitates collective action by promoting coordination and adherence to desired behavior. Communities with strong social capital are more likely to adopt water-saving practices during shortages due to the influence of social norms and reinforcing networks

(Putnam 2000). Secondly, social capital reduces transaction costs in everyday interactions and businesses. Trust, a key component of social capital, ensures that parties fulfill their obligations, reducing the need for monitoring and enforcement. Moreover, social capital promotes awareness of interconnections among individuals, fostering virtues like tolerance and empathy and discouraging socially unacceptable actions (Putnam 2000).

Furthermore, social capital enhances the flow of information, empowering individuals to address community needs and challenges effectively. Informed citizens can identify issues and devise solutions, contributing to community well-being. Additionally, social capital can increase the value of assets, goods, and services. Properties in vibrant neighborhoods with strong social networks may be more highly valued, and businesses in welcoming communities may thrive (Spacey 2018).

A critical review and analysis of Social Capital theories and arguments Social capital, like other forms of capital, can have both positive and negative

consequences depending on its application. A cohesive society, while powerful, might engage in actions with detrimental outcomes for all involved, demonstrating the complex nature of social capital’s impact (Spacey 2018).

However, Coleman’s concept of social capital has faced criticism. He is faulted for overlooking the difference between resources and individuals’ access to them through networks, and his rational action theory does not fully explain the various incentives among recipients and producers of social capital (Portes 1998). Furthermore, Coleman’s horizontal definition of social capital neglects structural disparities and power dynamics, failing to address vertical inequalities and gender-related socioeconomic inequities (Molyneux 2002).

Similarly, Putnam’s interpretation of trust as an aggregate measure of social capital has been criticized, as he links it to various factors like economic growth and democratic ethos without considering alternative causal possibilities (Portes 1998). Additionally, his failure to

account for human action within network structures and disregard for historical possibilities may lead to unforeseen liabilities or burdens arising from investments in human capital (Fukuyama 2001).

Conclusion

In conclusion, social capital plays a crucial role in enhancing individuals’ quality of life through support, collaboration, and economic implications. It fosters effective collaboration and resource distribution among groups and institutions, leading to increased incentives, norms, and knowledge acquisition. Empirical evidence suggests that high social capital positively impacts respect, dignity, academic success, and political activity. However, achieving desired outcomes from social capital relies on considering cultural, political, and socioeconomic factors in each society. Effective utilization of social capital necessitates aligning norms, values, culture, quality of life, and socioeconomic policies and strategies at the national level.

Bibliography

- Adler, P.S., and Kwon, S.W. “Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept.” The Academy of Management Review, 2002, pp. 17-40.

- Becker, G. S. Human Capital. University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Forms of Capital. Greenwood Press, 1986.

- Cheung, Chau-kiu, and Raymond Kwok-hong Chan. “Social Capital as Exchange: Its Contribution to Morale.” Social Indicators Research, 2010, pp. 205-227. 5. Claridge, Tristan. “Coleman on social capital – rational-choice approach.” Social Capital Research, 23 April 2015, https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/coleman-on social-capital-rational-choice-approach/.

- Coleman, J. S. Equality and achievement in education. Westview, 1990. 7. Coleman, James S. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology, 1988, pp. 95-120.

- Flap, H. Creation and returns of social capital. Routledge, 2004.

- Flora, Jan. “Social Capital and Communities of Place.” Rural Sociology, 1998, pp. 481- 506.

- Fukuyama, F. “Social capital, civil society, and development.” Third World Quarterly, 2001, pp. 7-20.

- ICPSR. “Social Capital Over Time and Across Generations.” 18 December 2021, https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/pages/instructors/ddlgs/guides/socialcapital/index.h tml.

- Krishna, N., and Uphoff A. “Mapping and measuring social capital through assessment of collective action to conserve and develop watersheds in Rajasthan, India.” In C. Grootaert and T. van Bastelaer (Eds.), Rajasthan.

- Lauer, Robert H. Social Problems and the Quality of Life. William C. Brown Co. Publishers, 1978.

- Letki, N. “Does diversity erode social cohesion? Social capital and race in British neighbourhoods.” Political Studies, 2008, pp. 99-126.

- Molyneux, M. “Gender and the silences of social capital: Lessons from Latin America.” Development and Change, 2002, pp. 167-188.

- Numbeo. “Quality of Life Index by Country 2019.” 26 December 2019, https://www.numbeo.com/quality-of-life/rankings_by_country.jsp?title=2019. 17. Portes, A. “Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology, 1998, pp. 1-24.

- Putnam, Robert. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster, 2000.

- Schuessler, Karl F., and Gene A. Fisher. “Quality of Life Research and Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology, 1985, pp. 129-149.

- Schultz, T. W. Investment in human capital: The role of education and research. The Free Press, 1962.

- Smith, Mark H., Lionel J. Beaulieu, and Glenn D.lsrael. “Effects of Human Capital and Social Capital on Dropping Out of High School in the South.” Journal of Research in Rural Education, 1992, pp. 75-87.

- Spacey, John. “12 Examples of Social Capital.” 18 August 2018, https://simplicable.com/new/social-capital.

- The World Bank. “GovData360.” 29 October 2021, https://govdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/ha5376100?indicator=41334&viz=line_c hart&years=2017,2019&indicators=944&compareBy=income.

- Uslaner, E. M. “The moral foundations of trust.” Cambridge University Press, 2002

- Veenhoven, Ruut. “Why Social Policy Needs Subjective Indicators?” Social Indicators Research, 2002, pp. 33-45.

- Walker, Alan, and Laurent van der Maesen. “Social Quality and Quality of Life.” Social Indicators Research Series, 2004.

- Whitham, Monica Marlene. “Living better together: The relationship between social capital and quality of life in small towns.” Program of Study Committee, 2007. 28. World Health Organization (WHO). “Quality of Life.” 18 December 2021, https://www.who.int/home/search?indexCatalogue=genericsearchindex1&searchQuer y=quality%20of%20life&wordsMode=AnyWord.